Note: This is a long post and it’s based on reflecting on a couple of years of observations in the venture industry. It’s a work-in-progress and I expect to update (last update 10 June) and refine the content, especially in the next week as I prepare for a talk I’m giving at the PreMoney conference in SF next week. It is published here in relatively raw form. Comments and feedback are welcome.

Prologue

In June of 2013, as I was putting together my thoughts for the K9 Ventures annual meeting, I took a step back and reflected on what I saw happening in “Venture Land”. Almost two years ago, in a private/closed meeting with K9 Ventures’ LPs, I claimed that:

- What was being referred to in the press as the “Series A Crunch” was not due to fewer Series A deals, but too many Seed deals. This over-funding at the seed-stage created an increased supply of companies looking for Series A. The Series A investors could afford to be more picky. So although the symptom was that it felt tougher to raise Series A, the cause was a little deeper than most people realized.

- There were massive late stage rounds as all the big funds wanted companies which already had traction. Low supply of companies with traction drove the valuations and deal sizes up. The risk here is what I refer to as the ‘Curse of Over-Capitalization’.

- Seed stage was super tough. Increased competition for Series A meant a company needed more traction. More traction meant more time. and therefore more capital.Additionally, the competition for and the cost of hiring people, especially in the San Francisco Bay Area, went up dramatically. While the infrastructure cost and startup costs may have declined, the operating costs increased. Together this means that Seed stage companies needed to run longer and at a higher expense structure, meaning they need to raise a lot more capital.

- A re-jiggering of deal stages and sizes had begun in 2013. In that presentation, I said that Seed is not the first round of financing any more and that K9’s investments were now primarily “pre-seed”.

- As it happens almost every few years, there was a new normal developing. The Venture Capital industry as a whole does a terrible job of properly naming so we end up keeping the same name, but changing the meaning. In 2013, when I wrote these slides (excerpt above) for my annual meeting, it was still early to tell whether my analysis of these early signals was going to be right or not. Mostly, I kept my opinion within a small closed group and let my LPs know that K9’s strategy was to *not* change our strategy despite the pressures of the market. I still wanted K9 to be the first institutional money in and work with “frighteningly early-stage” companies.

Over the next few months, I saw more and more signals that this shift was really happening. Another thing I noticed was that I was now referring companies that I had invested in at a “pre-seed” (capitalization intentional) stage over to folks who would previously be considered my peer venture funds doing Seed-stage investments. It was time to express my point of view publicly, so one afternoon in April 2014, I spent two hours in between meetings writing:

The New Venture Landscape. Please read it, If you haven’t already, as it lays the foundation for everything that follows herewith.

Fast-forward to June 2015, two years later, and now I feel that the change that I started to notice back in 2013, is here, and it’s here to stay. So in this post, I present the epilogue to The New Venture Landscape that highlights my take on what I think the venture landscape looks like today and what the implications are for founders, for GPs and for LPs.

The Epilogue

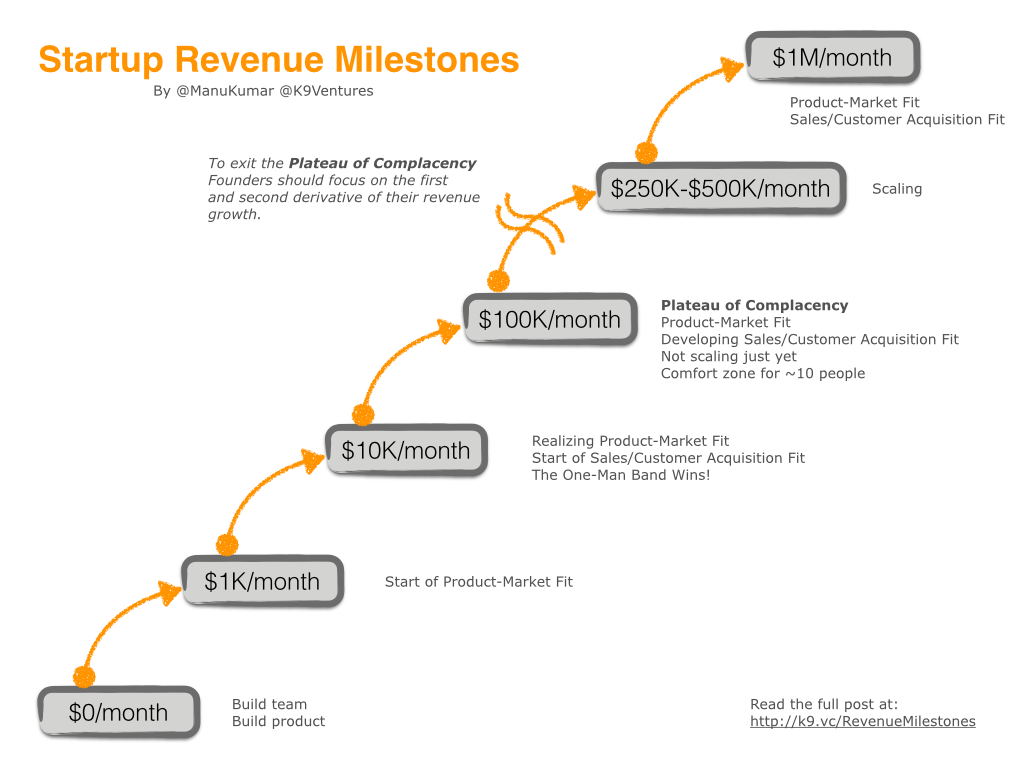

Seed is the New A

The seed round has ballooned. It’s now typically close to $2M and in some cases even approaching $3M. Valuations are rising to match. A typical seed round valuation may be $6M pre, raising $2M for an $8M post, or even as high as an $8M pre, raising $2M for a $10M post.

But here’s the kicker, the expectations of the Micro-VCs who were doing these seed rounds have changed as well!

As the check size increases, investors tend to look for more traction, established revenue models, proven unit-economics, and other metrics that were previously associated with later stage companies. Several of these Micro-VCs have almost slipped into this form of thinking, often without even realizing it. Almost like boiling a frog, the Micro-VCs who started out as “Super Angels” (See Investor Nomenclature, 2011 and Venture Spiral, 2008) writing $25K — $100K checks with personal money, are now managing funds which are $40M — $140M in size, some with multiple partners and are writing checks which are $750K — $1.5M. The change in thinking is natural and logical. The catch however is that some of these funds and their GPs haven’t admitted to themselves, to founders, and to LPs that their thinking and investing thesis has indeed changed (as it should). They are either in a state of denial or haven’t had the time to adjust their messaging yet.

With the increase in the size of the seed round and the change in expectations for that seed round, the Seed round is effectively what used to be the Series A.

Pre-Seed is the New Seed

If the Micro-VCs are looking for Series A-like metrics, what does a company do when it’s just getting started? If it doesn’t have the product fully baked yet? Or if the traction is not yet interesting enough to attract a full Seed round? Well, enter the Pre-Seed round, where the startup raises closer to $500K.

When I first started using the term ‘pre-seed’ in 2013, it was almost as a joke since I wanted to make a point that K9 was investing super early. At the time of writing the New Venture Landscape, I started to capitalize “Pre-Seed”. Over the course of the two years since, it’s been interesting to note how “Pre-Seed” has entered the vocabulary in venture. There are a now a handful of funds, K9 included, that are Pre-Seed funds in name and practice.

As more of the Micro-VCs and traditional VCs move further upstream, I wouldn’t be surprised if some partners from these funds venture out on their own to fill the gap they see at the Pre-Seed stage.

Implications for Founders

Raising a Seed round (new A) is harder because of the change in expectation for a round of this size. The good news for founders is that there is *so* much capital flooding in at the Seed stage and there are many new funds trying to play at this stage. The bad news is that once GPs have more money, they want to write a bigger check and for that bigger check they want to see things further along and somewhat de-risked.

Seed is not the first round of funding any more. Too many founders are still operating as such. They read the press about how Company X and Company Y raised $2M in their Seed round and start to think that that’s the amount that they should raise too. On far too many occasions I end up counseling founders that they’re not yet ready for raising $2M, but they may well be able to raise $500K now, use that to build the team and the initial product/prototype and then be able to raise a Seed round.

But don’t all investors say that they’re investing “early”? Well, yes they do. But as Andrew Carnegie said: “As I grow older, I pay less attention to what men say. I just watch what they do.” Founders should heed the advice from Andrew Carnegie, and also watch what investors do, not what they say. Look at the companies they’ve funded, how much they invested, and what stage the company was at. It’s not always easy to make sense of this, but it’s a better signal than relying on what investors say on their websites!

Implications for GPs

Stop living in denial. Spiraling up is a natural evolution of a venture fund, especially as you get more money and more partners. I refer to this as ‘The Venture Spiral’. Reflect on the stage you’re investing at and be sure that you’re staying within the bands of your competency (and ergo not riding the spiral up to a level of incompetency).

Reflect on what you’re doing and revisit your messaging to founders and to LPs accordingly.

Implications for LPs

Your early stage investment portfolio may no longer really be early stage. This is especially true if LPs have been long-time investors in Traditional VC funds. The Traditional VC funds have decidedly moved upstream (in general, although there are a few pointed examples of VCs doing early stage deals, even Pre-Seed deals). This in turn impacts the return profile that can be expected. That’s not to say that some firms won’t have great returns in the right deals, but overall across the industry, the Traditional VC returns will decline as a result of them moving upstream. My guess is that getting 2x-3x from a Traditional VC fund would be a great outcome. And it will be the Pre-Seed and Seed (new A) funds that will be more likely to have outsized returns on winners.

Micro-VCs are the new Series A investors. Several LPs have already recognized this and have made commitments to Micro-VC funds. For those LPs who haven’t entered this stage yet, they may well have missed the boat as the best funds that were going to emerge may have already been established.

The early-stage vacuum that existed in 2006–2007 led to the formation of “Seed” funds, is oddly enough re-emerging as the Micro-VCs who once dominated this space move upstream. Yes, history is repeating itself!). This means that there will still be a new crop of Pre-Seed funds that will emerge. There is an opportunity for LPs to pick the right Pre-Seed stage funds, but I certainly don’t envy their job as it’s not going to be an easy task.

Scaling venture capital breaks it. Venture capital is, and should remain, a boutique industry (read ‘The Venture Boutique,’ 2008). LPs who like to complain about the return from the venture asset class have no one to blame but themselves for it. As the assets under management increase, LPs want to make larger commitments to their best funds and managers and the smaller amounts don’t move the needle, but that is precisely what leads to the Venture Spiral.

The management fee structure provides a perverse incentive to GPs to increase the size of their funds. The founders of these funds are entrepreneurs in their own right and every entrepreneur has an innate desire to make things grow. Adding partners and staff, starts to give a false sense of scale. It all culminates in the fund move upstream and making larger initial investments than where they started (i.e. the Venture Spiral).

Too Much Capital

We’re in a very strange kind of environment in the venture world these days. There is too much capital coming into tech investing. A lot of this capital is coming from non-traditional geographies like China, Russia, Middle East, India. Tech companies generate a lot of buzz. In fact I’d argue that other than Hollywood, sports, and politics, tech and business probably garner more widespread interest around the world. This means that there is interest in tech-investing globally, especially focused on Silicon Valley startups. (I can attest to at least one incident of being told that there are people in India who want to invest in tech companies so they can go to cocktail parties and claim that they’re investors in some hot-tech company in Silicon Valley. Knowing the culture well, I find this entirely believable.)

Since access to investing in tech companies is limited, a lot of this capital is finding it’s way into new funds and, I’m going to guess, that it’s also working it’s way through direct investments in companies coming out of accelerator demo days and AngelList.

Another major factor at play here, which was well articulated by Mark Suster in The Changing Structure of the Venture Industry is that value creation today happens predominantly in private markets and not so much in public markets. In the 80s and 90s a company would go public when it hit $20M in revenue. Today, companies are going public with billions of dollars in revenue and in some cases staying private even when they have billions in revenue. The Wall Street investors have recognized this and have realized that they can not wait for a company to go public. They need to get positions in these companies much earlier. This is clearly evident in the large number of hedge funds and banks that we see participating in the growth stage rounds of tech companies.

For reasons I cannot explain (input welcome), the Wall Street money appears as if it is insensitive to valuations. The thinking is that since these companies will always be valued higher than the liquidation preference of the investment, therefore there is downside protection, and so they’re only playing for the upside. Worst case they get their money back, best case they hit a home run. There is an erosion of valuation discipline across all stages of venture capital right now.

Corporate investors that are also participating in late stage rounds. Interestingly these are mostly large Asian companies, but also some large US companies. For most new-age corporate investors if they don’t lose money, they’re in good shape. If they make money, then that’s just the icing on the cake. It’s a different way of thinking than how a VC would think. VCs are in the business to make money on their investments and doing that requires VCs to remember the importance of valuation discipline and understanding their entry point.

There is an influx of capital into Venture, and Venture as we know it is changing. It is effectively broadening. On one hand we’re still doing early stage (now Pre-Seed), but on the other hand since companies remain private longer and grow to sizes that are sometimes even beyond what we used to see in public markets, the venture capital has flexed and expanded.

Impact of Public Markets

Marc Andreessen (@pmarca) tweeted this recently…

![Andreessen tweet]()

… which made me think about this even more. Are we in a situation where it’s a case of a rising tide floats all boats? If the public markets do hit a road bump or worse a sinkhole, what will happen? For starters all the excess capital that is flushing into the venture market will dry up almost instantaneously. The ginormous valuations will crater and there will be a return to fundamentals and a correction, which I think is long over due.

As my kids would attest, I’m a self-proclaimed expert in bubbles, but only of the soapy kind. Bubbles are awesome. They’re so much fun to play with, fun to watch, but ultimately they pop. That’s true of soap bubbles and of economic bubbles. I don’t claim to profess any deep knowledge of the latter, but I will note that we’ve had an incredible run over the past 7 years since the doldrums of 2008.

If a correction does happen, several of the new funds that have been formed based on the “new capital” will find themselves in a precarious position for future funds. That will perhaps cause a rejiggering of deal sizes once again, but it’s clear that several of the micro-VC funds have now become franchises that will survive any such downturn. We’re living in a brave new world and we need to acknowledge that things have changed. The New Venture Landscape is here and it’s probably here to stay.

You can follow me on Twitter at @ManuKumar or @K9Ventures for the K9 Ventures related tweets. K9 Ventures is also on Facebook and Google+.

The post The Seeds Have Changed: An Epilogue appeared first on K9 Ventures.

(note, different from K9-use)

(note, different from K9-use) The lobby and private offices in the front of the building.

The lobby and private offices in the front of the building. The main conference room with the cool acoustic foam ceiling.

The main conference room with the cool acoustic foam ceiling. The container forms the centerpiece of The Kennel.

The container forms the centerpiece of The Kennel. The line of sight along the left edge of the container leads directly into the event space.

The line of sight along the left edge of the container leads directly into the event space. The container cargo doors are usually closed, but can be opened when needed.

The container cargo doors are usually closed, but can be opened when needed. Light permeates the space via the roll up glass garage doors in the rear.

Light permeates the space via the roll up glass garage doors in the rear. The interior of the container conference room.

The interior of the container conference room. View from the whiteboard wall in the lounge space.

View from the whiteboard wall in the lounge space. The main entrance to the container is a sliding glass door.

The main entrance to the container is a sliding glass door. The container and the bleachers as viewed from the lounge space.

The container and the bleachers as viewed from the lounge space. The bleachers tie in with the event space to provide for additional seating.

The bleachers tie in with the event space to provide for additional seating. The homey lounge area can double as an interactive work area.

The homey lounge area can double as an interactive work area. Ping-pong challenge in the recreation space.

Ping-pong challenge in the recreation space.

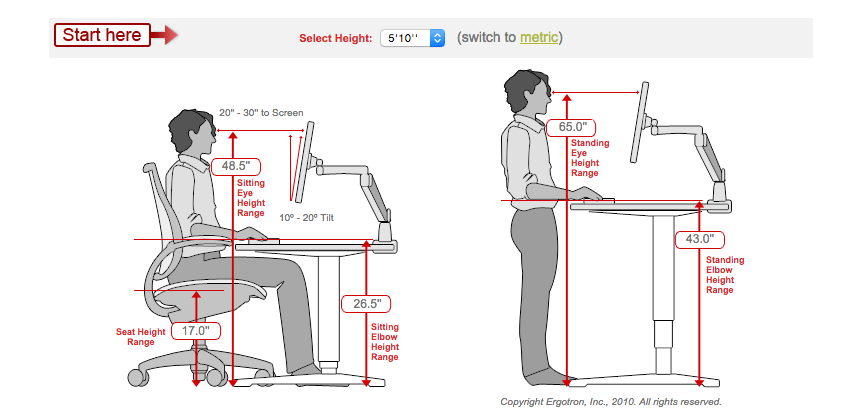

IKEA-hack standing desk

IKEA-hack standing desk